Introduction: Were We Really Caught Off Guard?

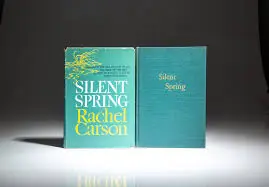

When people ask, “Did anyone warn us before modern environmental disasters?” the conversation usually lands on Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. And yes, it was revolutionary.

But here’s the truth: Silent Spring wasn’t the first environmental warning. It was simply the one we finally listened to.

Long before the 20th century environmental movement, scientists, writers, physicians, and even city officials were raising red flags about pollution, deforestation, poisoned water, and collapsing ecosystems. These warnings flickered through history like signal fires in the dark. Most were ignored. Some were suppressed. A few nearly changed everything.

Let’s step back and trace those forgotten alarms.

Before Environmentalism Had a Name

Ancient Concerns About Air and Water

Environmental anxiety is not a modern invention. In ancient Rome, writers complained about toxic air from smelting operations. Philosophers noted how urban crowding fouled water supplies.

Even then, people understood a simple truth: human activity could degrade nature.

Early Regulations That Sound Surprisingly Modern

Medieval cities enacted laws restricting waste dumping into rivers. In 14th century England, burning coal in London was temporarily banned because of choking smoke.

These weren’t symbolic gestures. They reflected a growing awareness that unchecked pollution harmed public health.

The 18th Century: Forests on the Brink

Timber Shortages and Ecological Fear

By the 1700s, European thinkers began worrying about deforestation. Timber fueled ships, buildings, and industry. Forests were disappearing at alarming rates.

German scholars even coined early ideas resembling sustainability, arguing forests should be managed to ensure continuous yield. The principle was simple: don’t harvest more than nature can regenerate.

Colonial Expansion and Resource Anxiety

As empires expanded, so did resource extraction. Observers documented soil depletion in colonies and warned that agricultural practices could permanently damage land.

Some policymakers listened briefly. Most prioritized economic growth.

The 19th Century: Industrial Smoke and Public Outcry

The Rise of Urban Pollution

The Industrial Revolution transformed cities into engines of production and smoke. Coal powered factories, trains, and homes. It also blackened skies.

Writers described soot so thick it dimmed daylight. Physicians linked respiratory illnesses to industrial emissions long before modern air quality science.

Early Conservation Voices

Figures like George Perkins Marsh argued in the mid-1800s that human activity could alter climate and geography. His book Man and Nature warned that deforestation and land misuse had long-term consequences.

He wasn’t dismissed as eccentric. He was simply overshadowed by the momentum of industrial expansion.

Rivers That Caught Fire Before We Noticed

Waterways as Industrial Dumping Grounds

Long before famous 20th century river fires, waterways were heavily contaminated. Industrial waste, sewage, and chemicals flowed freely into rivers.

Communities downstream often reported fish die-offs and foul-smelling water. Local protests emerged periodically.

Why These Warnings Faded

The problem wasn’t lack of evidence. It was scale.

Environmental damage felt localized, manageable, temporary. People assumed rivers would cleanse themselves, forests would regrow automatically, and smoke would drift away harmlessly.

Optimism became a convenient blindfold.

Agricultural Warnings Before Pesticide Debates

Soil Exhaustion and the Dust Bowl

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, agronomists warned about intensive farming practices. Over-plowing and monocropping stripped soil of nutrients.

Those concerns culminated in the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, when massive dust storms devastated American farmland. The crisis proved what earlier critics had argued: land mismanagement carries consequences.

Early Chemical Concerns

Even before synthetic pesticides dominated agriculture, scientists questioned the long-term impact of chemical fertilizers and industrial runoff.

The pattern was familiar:

- Innovation arrives

- Productivity increases

- Side effects emerge

- Warnings surface

- Economic priorities override caution

History repeats this rhythm with uncomfortable precision.

Why Silent Spring Resonated Differently

The Power of Narrative

So why did Silent Spring succeed where others failed?

Rachel Carson combined scientific rigor with storytelling. She painted a vivid picture of a world without birdsong. That emotional framing shifted public consciousness.

Earlier warnings were technical or localized. Carson’s message felt universal.

Timing and Media

By the 1960s, mass media amplified ideas rapidly. Television and national newspapers carried environmental concerns into living rooms.

The public was also primed. Postwar prosperity had created space to question unchecked industrial growth.

The Pattern of Ignored Warnings

Economic Growth Versus Ecological Limits

Across centuries, a consistent tension appears. Economic expansion often drowns out ecological caution.

Warnings were dismissed not because they lacked merit, but because they threatened profit or convenience.

The Psychology of Delayed Consequences

Environmental damage rarely feels immediate. It unfolds slowly, across decades. Humans struggle with delayed risk. We respond to visible disasters more readily than gradual decline.

This explains why many early environmental warnings faded into obscurity.

What We Can Learn from Forgotten Voices

Listening Earlier Matters

When we examine historical environmental warnings, a pattern emerges: the science was often sound. The political will was not.

Recognizing this helps us evaluate modern climate and sustainability debates with sharper awareness.

Prevention Is Cheaper Than Repair

History shows that ignoring early warnings increases long-term costs. Reforestation, soil restoration, and pollution cleanup require immense resources once damage is done.

The lesson is pragmatic, not sentimental.

Rethinking Environmental History

We often frame environmental awareness as a modern awakening. But it’s more accurate to see it as a recurring whisper that grows louder with each generation.

Silent Spring was not the first alarm bell. It was the one that finally echoed far enough.

And that realization shifts how we understand environmental progress. It’s not a sudden enlightenment. It’s a slow accumulation of voices that refused to stay quiet.

Conclusion: The Warnings Were Always There

When we ask whether earlier generations understood environmental risks, the answer is yes. They observed polluted rivers, vanishing forests, and degraded soils. They wrote about them. They legislated occasionally.

What they lacked was sustained collective action.

The powerful takeaway is this: history is full of early warnings. Our responsibility is not just to hear them, but to respond before they become crises.

The next environmental whisper might already be echoing. The real question is whether we will recognize it in time.

FAQs

What environmental concerns existed before Silent Spring?

Concerns included deforestation, urban air pollution, contaminated rivers, soil depletion, and early chemical exposure risks.

Did ancient civilizations regulate pollution?

Yes. Ancient Rome and medieval European cities implemented laws addressing waste disposal and air pollution.

Why were early environmental warnings ignored?

Economic priorities, limited scientific tools, and the slow pace of environmental damage often overshadowed concerns.

Was climate change discussed before the 20th century?

Some 19th century thinkers speculated that deforestation and industrial activity could alter climate patterns, though the science was still developing.

How did Silent Spring differ from earlier warnings?

It combined scientific evidence with compelling narrative storytelling, reaching a broad audience during a time of growing environmental awareness.