Introduction: The Quiet That Spoke Volumes

Imagine opening a diary from 1918, expecting a world at war and a pandemic killing millions—and finding hardly a word about the flu. This silence reveals the complexity of historical memory and pandemics, showing how a global catastrophe quietly passed through personal journals.

My perspective is this: the silence was not an accident. Fear of stigma, social norms, and the limits of language created a collective quiet. Diaries, letters, and memoirs were full of daily life—but missing the words that historians today wish had been there. Understanding this silence gives us a lens into how humans process trauma, social pressure, and mortality.

What Was the Great Silence of 1918?

- The Great Silence refers to the lack of diary entries or personal accounts documenting the 1918 influenza pandemic, despite its unprecedented mortality.

- Historians estimate 50 million deaths worldwide, yet most first-hand accounts barely mention it.

- This paradox raises questions about memory, trauma, and social priorities.

Who Experienced the Great Silence Firsthand?

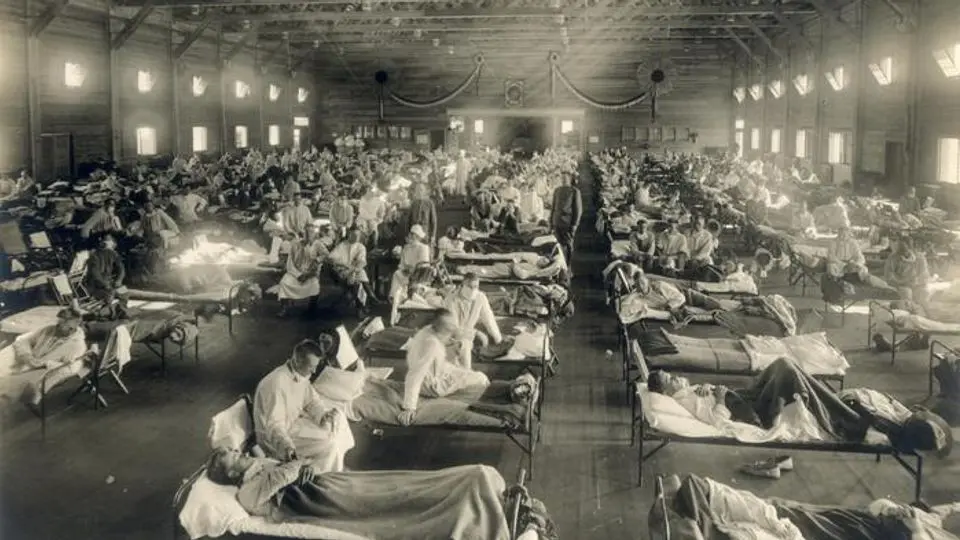

- Ordinary citizens: urban workers, farmers, and families grappling with sickness and scarcity.

- Frontline medical staff: doctors and nurses facing overwhelming numbers but constrained by social decorum in diaries.

- Children and teenagers: often silent witnesses, their observations filtered through adult interpretations.

Even in heavily affected areas, personal writing minimized the impact of the flu, reflecting social and emotional pressures.

Why Was It Barely Mentioned in Diaries?

Fear and Stigma

- Being sick could invite suspicion or ostracization.

- People feared spreading panic or shame.

- Diaries, though private, were often read by others, reinforcing self-censorship.

Normalization of Suffering

- Communities had endured war, poverty, and loss.

- The flu became “another hardship”, less noteworthy than expected.

Lack of Language

- Many writers lacked words to describe scale or emotion.

- The enormity of the pandemic exceeded narrative conventions in personal journals.

When and Where Was the Silence Most Noticeable?

- Urban centers: large outbreaks often overwhelmed record-keeping.

- Rural areas: lack of literacy or written culture meant fewer diaries existed.

- Family letters: even intimate correspondence often avoided explicit flu discussion.

The silence wasn’t universal, but it was strikingly consistent across regions and social classes.

Global Events Concurrent with the Great Silence

- End of World War I: the armistice in November 1918 dominated attention.

- Political upheaval: revolutions in Europe, civil unrest, and economic collapse.

- Diaries reflect war, political events, and food scarcity, but rarely the flu itself.

Where Can Original Diaries from 1918 Be Found?

- Library of Congress – Diary Collections

- National Archives (UK & US)

- University special collections (Harvard, Yale, Oxford)

- Local historical societies

Many entries focus on daily chores, letters to family, and social life—the pandemic is often absent.

How Did the Silence Affect Daily Life and Communication?

- Social interaction: illness was acknowledged through absence or rumor, not explicit discussion.

- Community memory: collective trauma persisted, but the stories were coded or lost.

- Historical reconstruction: historians rely on death records, newspapers, and medical logs to compensate for diary omissions.

Factors Contributing to Avoiding Written Mention

- Cultural expectations: stoicism and privacy were valued.

- Overwhelm: the scale of illness made detailed journaling difficult.

- Focus on survival: day-to-day survival left little room for reflection.

- Fear of judgment: writing about sickness could appear weak or alarming.

Who Documented Life During Global Crises in 1918?

- Military personnel writing official reports

- Clergy maintaining parish records

- Local government clerks recording deaths and quarantines

These accounts are more complete than personal diaries but lack emotional texture, highlighting the contrast between formal documentation and intimate silence.

A Personal Insight: Why Silence Can Be Loud

In my observation, the Great Silence is not emptiness—it is expression by omission. Diaries don’t need to mention the flu to convey fear, grief, and adaptation. Historians reading the “silent” entries can detect:

- Subtle shifts in daily routines

- Notes of absence or unexplained deaths

- Emotional undertones in mundane events

Silence itself becomes a powerful historical signal.

Can Studying the Great Silence Help Us Understand Historical Memory?

Yes. By examining what isn’t written, we learn about:

- Cultural priorities

- Trauma processing

- Social pressures and self-censorship

- Intergenerational memory gaps

The Great Silence teaches us that history is both what is recorded and what is omitted.

Conclusion: Listening to the Unspoken Past

The 1918 flu pandemic killed millions, yet diaries remained largely silent. This silence—deliberate, instinctive, or circumstantial—reveals human coping strategies, social norms, and the limits of narrative.

In revisiting this period, we understand that absence can speak as loudly as presence. Historians must read between the lines, piecing together lives affected by catastrophe without the comfort of personal testimony.

The Great Silence reminds us that history is not only written in words—it is etched in omission, in the gaps that force us to look closer, listen harder, and think critically.

FAQs

FAQ 1: What was the Great Silence of 1918?

The Great Silence of 1918 refers to the near absence of mentions of the influenza pandemic in diaries. Studying it provides insights into historical memory and pandemics and how societies record—or omit—trauma.

FAQ 2: Who experienced the Great Silence firsthand?

Ordinary citizens, medical staff, and children lived through the pandemic. Their diaries, letters, and memoirs offer clues about historical memory and pandemics, showing what people chose to document or leave unsaid.

FAQ 3: Why did people choose not to write about major events in 1918?

Fear of stigma, emotional overwhelm, and the social expectation of stoicism made people reluctant to record illness and death in personal writings.

FAQ 4: Where can historians find evidence of the 1918 flu if diaries are silent?

Historians turn to official records, newspapers, hospital logs, and municipal death registries, as well as coded references in personal diaries and letters.

FAQ 5: Can studying the Great Silence help us understand modern crises?

Yes. It shows how humans may underreport trauma, censor themselves, or normalize suffering, which is valuable when analyzing modern diaries, blogs, or social media during global events.