Introduction

Have you ever wondered how people organized their thoughts before Amazon, libraries on every corner, or even printed books as we know them today? Before self-help shelves, productivity gurus, and viral quote threads, there was something quieter—but arguably more powerful. It was called the commonplace book, a practice central to Commonplace Books Philosophy.

In my own understanding, long before modern self-help literature and long before books became cheap and abundant, people didn’t just read ideas—they collected them. Scholars, politicians, philosophers, clergy, and everyday thinkers kept handwritten notebooks where they stored quotes, reflections, arguments, and moral lessons. These were not diaries. They were intellectual toolkits.

If modern self-help books promise transformation through consumption, commonplace books promised growth through engagement. And that difference matters more than we realize.

What Is a Commonplace Book, Really?

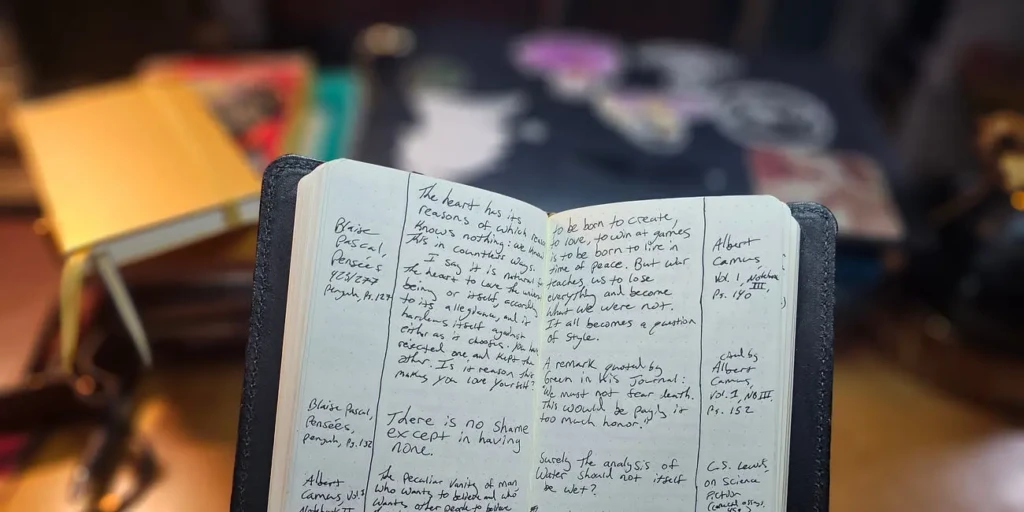

At its simplest, a commonplace book was a personal notebook where someone copied passages from books, sermons, letters, and conversations. But that definition is almost misleading in its modesty.

A true commonplace book was:

- A personal knowledge system

- A moral compass in written form

- A thinking partner, not a memory dump

Unlike journals, which tracked daily life, commonplace books tracked ideas. You didn’t write what happened to you. You wrote what shaped you.

In philosophy, the commonplace book functioned as an external mind—a place where arguments were tested, refined, and revisited over years, sometimes decades.

Who Kept Commonplace Books—and Why So Many Did

If you imagine commonplace books as dusty relics used only by elite scholars, think again.

From Students to Statesmen

Commonplace books were kept by:

- University students learning rhetoric and philosophy

- Clergy preparing sermons

- Lawyers building arguments

- Politicians sharpening moral reasoning

- Poets experimenting with language

John Locke, Francis Bacon, Thomas Jefferson, John Milton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge—all kept commonplace books. Even Nietzsche, who distrusted books as finished authorities, relied heavily on notebooks to fragment, question, and reconstruct ideas.

The reason was practical: books were rare, expensive, and often inaccessible. If you encountered a powerful idea, you had to preserve it yourself.

When Commonplace Books Became Popular

The practice dates back to classical antiquity, but it flourished between the 16th and 18th centuries.

This was a period when:

- Printing existed, but books were still scarce

- Education emphasized rhetoric and moral philosophy

- Memory and personal reasoning were prized skills

Students were actively taught how to keep commonplace books. In fact, many universities required it.

You weren’t expected to memorize everything. You were expected to curate wisdom.

How Commonplace Books Were Organized

Here’s where things get fascinating.

Most commonplace books weren’t chronological. They were thematic.

Writers organized them by headings such as:

- Virtue

- Power

- Love

- Politics

- Religion

- Death

- Knowledge

Under each heading, they added quotes, thoughts, and arguments over time. Some even cross-referenced entries—an early form of hyperlinking.

John Locke famously designed an indexing system so complex it resembles a primitive search engine.

This wasn’t passive note-taking. It was intellectual architecture.

Why Commonplace Books Were Not Diaries

This distinction is crucial.

A diary answers the question: What happened to me?

A commonplace book answers: What do I think about what happens in the world?

Diaries focus inward. Commonplace books look outward, then loop back inward with analysis.

That’s why philosophers preferred them. Philosophy isn’t about feelings alone—it’s about tested ideas.

The Philosophical Power of Commonplace Books

So why were these notebooks so central to philosophical thinking?

Because philosophy thrives on:

- Comparison

- Contradiction

- Repetition

- Slow digestion of ideas

A commonplace book allowed thinkers to place Aristotle next to Augustine, or a Biblical proverb beside a political speech. Meaning emerged in the collision.

This method trained the mind to synthesize rather than merely absorb.

Professions That Relied on Commonplace Books

Certain professions leaned heavily on this practice:

Clergy

Sermons required moral clarity and persuasive structure. Commonplace books provided both.

Lawyers

Arguments were built by collecting precedents, maxims, and rhetorical strategies.

Politicians

Statesmen used them to shape political philosophy and ethical leadership.

Writers and Poets

They mined language, metaphor, and rhythm from earlier works.

In every case, the commonplace book functioned as a private university.

Famous Commonplace Books That Survived

Some commonplace books are now historical artifacts:

- John Milton’s theological notes

- Thomas Jefferson’s moral extracts

- Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations (arguably a refined commonplace book)

What’s striking is how unfinished they feel. They were never meant for publication. They were meant for use.

A Contrarian Observation: Why Commonplace Books Declined

Most explanations blame the rise of printed books and formal education. That’s true—but incomplete.

A closer look reveals something deeper: we stopped valuing intellectual ownership.

As books became abundant, we outsourced thinking to authors. Instead of wrestling with ideas, we consumed conclusions.

Self-help books didn’t replace commonplace books. They reversed their logic.

Commonplace books asked: What do you think?

Self-help books often answer: Here’s what to think.

Were Commonplace Books Early Self-Development Tools?

Absolutely—but not in the way modern self-help frames growth.

They didn’t promise quick transformation. They demanded patience.

Growth came from:

- Rewriting ideas in your own words

- Revisiting them over years

- Letting contradictions sit unresolved

This was self-development through discipline, not motivation.

What Nietzsche Really Meant About Books

Nietzsche warned against reading too much—but he wasn’t anti-thinking. He was anti-passivity.

His notebooks show a mind constantly breaking ideas apart and rebuilding them. In that sense, he embodied the commonplace tradition, even while criticizing its era.

Books were raw material. Thinking was the goal.

Can We Revive the Practice Today?

Not only can we—we probably should.

Modern tools like Notion, Obsidian, and even simple notebooks make this easier than ever. The danger isn’t lack of access. It’s lack of engagement.

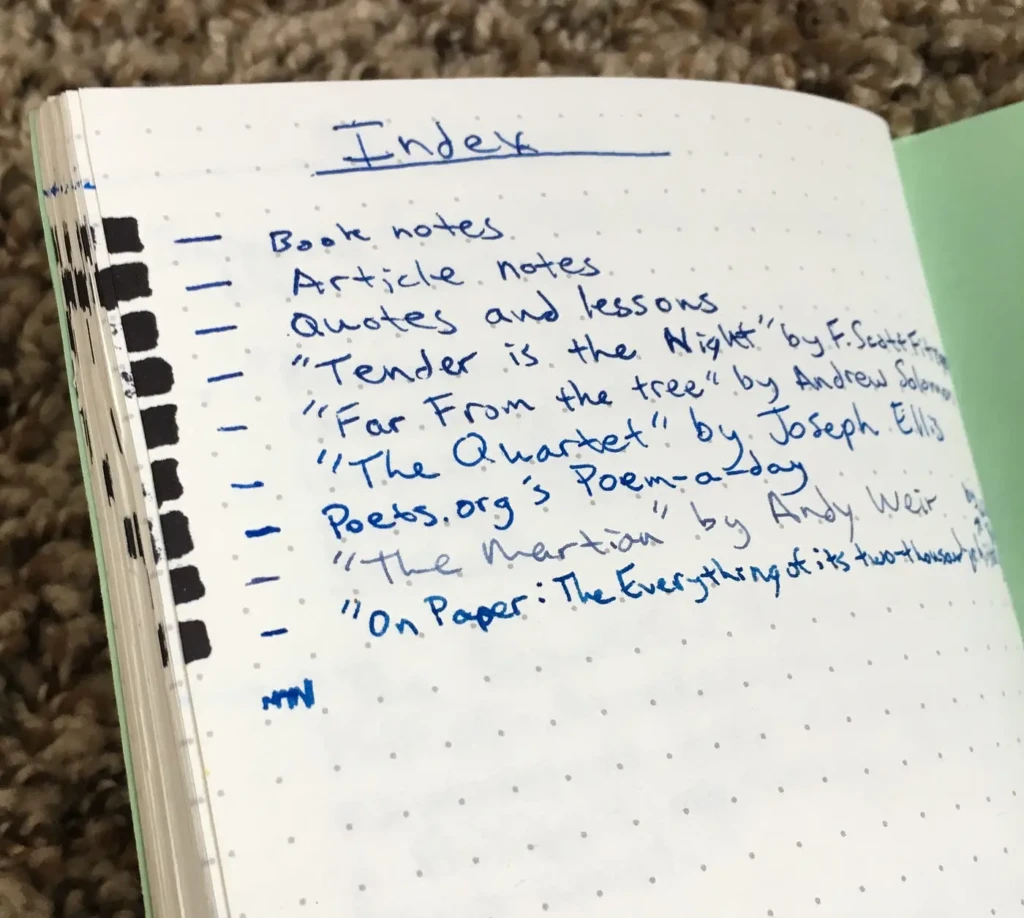

A modern commonplace book might include:

- Quotes from books and podcasts

- Personal reflections

- Contradictions you haven’t resolved yet

- Questions without answers

The format matters less than the mindset.

How to Start Your Own Commonplace Book (Practically)

If you’re curious, start simple:

- Choose a medium (notebook or digital)

- Create broad themes, not rigid categories

- Copy only what genuinely provokes thought

- Add your own commentary

- Revisit entries regularly

If it doesn’t change how you think, you’re doing it wrong.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

We live in an age of endless information and shallow understanding.

Commonplace books remind us that wisdom isn’t about volume—it’s about relationship. A relationship with ideas, tested over time.

Before self-help books taught us to optimize ourselves, commonplace books taught us to understand ourselves.

That might be the upgrade we actually need.

Conclusion: The Lost Art of Thinking in Public with Yourself

Commonplace books were never about nostalgia. They were about responsibility—the responsibility to think clearly, slowly, and honestly.

In a world obsessed with answers, they honored questions.

And maybe that’s why they still matter.

FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the commonplace book in philosophy?

In Commonplace Books Philosophy, it is a personal system for collecting, organizing, and reflecting on philosophical ideas rather than recording daily life.

FAQ 2: Who were the most famous users of commonplace books?

John Locke, Francis Bacon, Thomas Jefferson, John Milton, and many Enlightenment thinkers.

FAQ 3: How is a commonplace book different from note-taking?

Note-taking records information. Commonplace books transform information into understanding.

FAQ 4: Are digital tools suitable for commonplace books?

Yes, as long as they encourage reflection, synthesis, and revisiting ideas.

FAQ 5: Can commonplace books replace self-help books?

They don’t replace them—but they cultivate deeper, longer-lasting growth.