Introduction: The 19th Century’s Patent Medicine Craze Shaped Modern Advertising

You might think of modern advertising as a creature of television spots, social media influencers, and data analytics — but the blueprint for much of that practice was already in place long before the first radio ad or billboard. The roots of modern advertising lie in the 19th century marketing techniques pioneered during the patent medicine craze — that wild, unregulated trading ground of cure‑alls, tonics, and miracle elixirs that dominated 19th‑century consumer life.

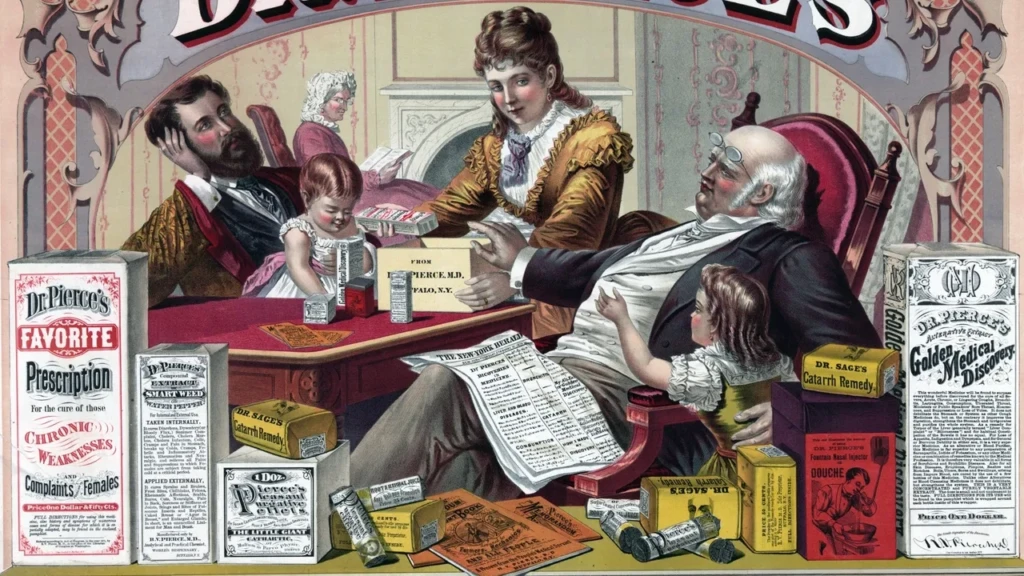

These “nostrum‑mongers,” as they were often called, sold everything from remedies for female weakness to tonics for tuberculosis — despite frequently having no real medical value. What they did have was an uncanny knack for selling stories, emotions, and belief. And in doing so, they laid down the essential architecture of modern advertising. (news.cornell.edu)

Why Patent Medicines? The Perfect Storm for Marketing

Before the industrial era, most medicines were dispensed by local apothecaries and trusted physicians. But the 19th century saw an explosion of industrial manufacturing, mass newspapers, and rapidly expanding literacy. Patent medicines — often mislabeled and unregulated — rose to fill a gap in public health and consumer imagination. They promised hope in a bottle while mainstream medicine still relied on practices like bloodletting and purging. (Smithsonian Institution)

People across classes bought these medicines — from rural farmers to urban merchants. Why? Two big reasons:

- Fear and uncertainty about disease and poor medical options.

- Wishful belief in quick cures marketed with confidence and flair.

This meant one simple thing: there was an audience desperately primed for messages that promised change. Modern advertising as we know it emerged by learning how to reach and persuade that audience. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

Patent Medicines: Not Really “Patent,” but Pure Marketing

Interestingly — and somewhat misleadingly — most patent medicines weren’t patented in the true legal sense. The term referred more to a trade practice than to the actual registration of ingredients. In part, the label was borrowed from products that were patented or licensed, and utterly embraced because it sounded scientific and authoritative. (AIHP)

You can almost hear the sales pitch: “Patented! Endorsed! From revered secret formulas!” The branding worked. In truth, manufacturers protected their product names and label art but rarely had to disclose what’s inside. ■

From Print to Persuasion: Advertising Techniques Born in the Patent Medicine Era

So what exactly did patent medicine promoters invent — or refine — that we still see in advertising today?

1. Branding and Distinctive Packaging

Companies realized early that distinct bottles and labels helped consumers remember their product and trust its “look.” This is the ancestor of what we now call brand identity. They also registered trademarks — so you knew you were buying Bigelow’s Extract or Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills. (University of South Carolina)

2. Mass‑Market Newspaper and Magazine Ads

By mid‑19th century, newspapers were swelling with patent medicine ads — so much so that by the 1890s, one‑sixth of all print advertising came from patent drug companies. This influx fundamentally changed media economics: newspapers were no longer just sellers of content — they gathered audiences for advertisers. (DigFir)

Think about that: the relationship between advertising and media revenue that we still debate today began with “snake oil” ads.

3. Emotional and Sensational Copy

Modern direct‑response marketing always tries to tap into emotion. Patent medicine advertising perfected early versions of this by:

- Promising relief for fear‑laden ailments

- Using dramatic testimonials

- Painting grim pictures of disease and then offering salvation

Ads regularly used fear (fear of death, disease progression), aspiration (a healthier, happier family), and social proof (celebrity testimonials, even politicians!). (KU ScholarWorks)

Sound familiar? It should — emotional triggers are at the center of persuasive ads today.

4. Trade Cards and Collectibles

Before full‑color magazine spread, there were trade cards — vividly illustrated pieces comparable to modern collectible promo cards or even Instagram posts. People saved them, shared them, and associated them with their own lives. This wasn’t just advertising; it was early brand engagement. (Weill Cornell Medicine Library)

5. Promotion Through Almanacs and Freebies

Patent medicine companies printed their own calendars and almanacs and gave them away — a technique borrowed straight into modern content marketing. These almanacs weren’t just ads; they were useful items with embedded marketing designed to keep your brand on someone’s wall all year long. (nlm.nih.gov)

The Birth of National Advertising Networks

With the expansion of railroads, telegraph lines, and printing technologies, patent medicine promoters developed what was essentially the first national advertising network. Medicines were advertised across states, often in dozens of newspapers simultaneously. They triggered the concept that a product could be known from Maine to Mississippi. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

This was groundbreaking. Before this, most commerce was local, word‑of‑mouth supported. But patent medicine campaigns reached into cities and frontier towns alike. And they didn’t just sell a bottle — they sold a belief.

Authority Without Science: A Contrarian Look at Effectiveness

Here’s a tension that fascinates me as a content strategist: advertising doesn’t have to be true to be persuasive — it needs to feel credible. In the patent medicine era, manufacturers didn’t need scientific backing. They used authority by association (doctor‑like titles, testimonials from “experts”), just like some modern marketing campaigns use celebrity endorsements or pseudo‑scientific language to sell wellness products today.

This flawed credibility didn’t just sell medicines — it taught advertisers how story and authority perception can outweigh substance. That’s why you still see brands today emphasizing trust signals (awards, certifications, “doctor recommended”), even when the evidence is thin. The patent medicine era didn’t invent this — but it perfected it. (Encyclopedia.com)

Backlash and Regulation: The Other Side of Advertising History

If the marketing tactics of patent medicines were innovative, they were also dangerous and deceptive. Many products contained addictive or harmful substances like alcohol, cocaine, morphine, and mercury — yet promised cures for everything. (news.cornell.edu)

Journalist Samuel Hopkins Adams’ 1905 exposés in Collier’s Weekly highlighted these deceptive claims and helped push the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This was a turning point: suddenly, government began to regulate medical claims and advertising honesty — a predecessor to the FDA’s role today. (Wikipedia)

This regulatory push was a direct response to advertising, not science. The lesson here echoes: when marketing overreaches, pushback reshapes the rules — just as issues with digital privacy have shaped modern data‑tracking laws.

Where You See the Legacy Today

If you’re reading this article because you’re curious about advertising history, you’ve probably already seen echoes of the patent medicine era in:

- Brand storytelling and fear→solution framing

- Mass media advertising economics

- Use of collectible promotional items

- Emphasis on trust signals in messaging

- Cross‑channel campaigns (print, mail, live events)

And if you’ve ever noticed how much health and wellness products still tap similar emotional levers — you’re seeing the patent medicine legacy alive and well in the 21st century. (Marketing Scoop)

Conclusion: What We Must Remember

The patent medicine era was messy, often harmful, and driven by greed — but it was also the crucible in which many core advertising practices were forged.

In trying to persuade millions to buy what were essentially unproven elixirs, promoters invented:

- Branding as identity

- Advertising as mass communication

- Emotional persuasion as central to marketing

- Audience segmentation via print and giveaways

- The idea that a product can be “sold” to millions with a unified message

These innovations underlie everything from today’s digital ads to the celebrity endorsements you see during the Super Bowl.

Ultimately, the lessons of the patent medicine era show us how 19th century marketing techniques still influence how brands tell stories, build trust, and persuade audiences today.

FAQs

1. What exactly was a patent medicine?

A patent medicine was a widely marketed, over‑the‑counter remedy claiming to cure many ailments. Most weren’t patented in the legal sense and often contained unlisted ingredients like alcohol or narcotics. Importantly, the way these medicines were promoted pioneered 19th century marketing techniques that still influence advertising today. (news.cornell.edu)

2. Why did these medicines become so popular despite the risks?

Because medical science was still developing, people lacked reliable treatments and were desperate for remedies — and these products were heavily marketed with persuasive language and testimonials. (Smithsonian Institution)

3. When did advertising begin to change because of patent medicines?

By the late 19th century, patent medicine advertising dominated newspapers and almanacs, prompting media systems to adapt and creating early forms of national campaigns. (nlm.nih.gov)

4. What role did regulation play in shaping advertising standards?

Public backlash against misleading claims in the patent medicine era helped spur the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, laying groundwork for future advertising and drug regulations. (Wikipedia)

5. How did traveling medicine shows contribute to advertising?

These shows combined entertainment and product promotion, teaching advertisers the power of live engagement and experiential branding — something modern marketers replicate in events and experiential campaigns. (Encyclopedia.com)